In the fall of 2022, I was nearing the end of a year’s continuous chemo- and immunotherapy for cancer. András Schiff was to play the Goldberg Variations in Vancouver, and I much wanted to hear his performance. What occurred is related in this article.

Three years later, in July of 2025, my health had begun to stabilize, although I was still in medical therapy for cancer. I was reading Madeleine Thien’s Do Not Say We Have Nothing. I find Thien’s novel often very moving. And her interweaving of music, notably the Goldberg Variations, very satisfying and deft, as she weaves music into her twofold stories. Or, is it that the stories weave around the music? The first reference is to Bach’s 4th sonata for violin and piano, the second to Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto, the third to the 7th canon of the Goldberg Variations, followed immediately by a reference to its 9th variation. When I went to the Variations themselves, it was as if I were hearing them for the first time. Soon afterwards, I fully realized I needed to effect a reconciliation and a moving forward in the present for the future.

For August, I designed an introspective process for the beginning of each day of that month to resolve several important personal ambiguities and ambivalences. It was of three parts: a free-form meditation, followed by an adaptation of the Jesuitical examen; and as the third part of this process, I decided to listen successively, each morning, to one of the thirty variations that comprise Bach’s Goldberg Variations, and then write a brief impression of my experience of it. Adding the aria, this matched exactly the thirty-one mornings of that month.

The Goldberg Variations is music for sleepless nights.

Schiff: All instruments try to imitate the human voice.

Schiff: We live in such a noisy world and we should treasure all opportunities to get away from it.

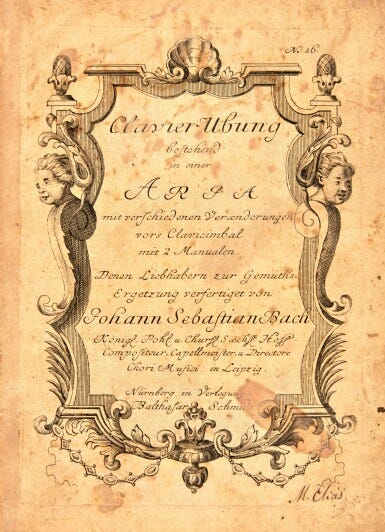

A masterpiece, composed when Bach was 55, an advanced age for his time, and the greatest of his compositions for cembalo, in this instance a harpsichord with two manuals. The piano did not yet exist in Bach’s time. András Schiff argues that the music settles into four groups: 1) variations 1-10; 2) 11-15; 3) 16-22; and 4) 23-30; and I tend to agree with his formulation.

We know that the aria is not Bach’s but a French dance piece of unknown authorship, but what continues to strike me is that he chose the aria upon which to set the thrity variations of 1741 after he had written it into his wife’s, Anna Magdalena’s, notebook in 1725. According to Schweitzer it is the sarabande that follows the song “Bist du bei mir,” from Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel’s opera Diomedes. When one knows of the lyrics even more poignancy emerges in relation to the later aria.

Bist du bei mir, geh ich mit Freuden / Zum Sterben und zu meiner Ruh. / Ach, wie vergnügt wär so mein Ende, / Es drückten deine schönen Hände / Mir die getreuen Augen zu.

If you are with me, I go with joy / To death and to my rest. / Ah, how happy would my end be, / If your beautiful hands / would close my faithful eyes.

Albert Schweitzer, in the chapter on the clavier pieces, in his first book on Bach wrote that it “is impossible to take to the work at a first hearing. We have to get to know it, and to understand the music of Bach’s last period, in which the interest resides not so much in the charm of this or that melodic part, as in the free and masterly working out of the ideas.”

The demonstration of the importance of the opening aria’s 32 bass notes, in their two halves, each repeated, is explained clearly by a number of musicians, and the one I have found the most helpful is Schiff’s from his Berlin recital. He emphasizes that in Bach’s music there is not melody and accompaniment, but independent voices, Stimmen, of equal importance. Moreover, as the piece includes two statements of the aria, at the beginning and at the end of the work, and thirty variations upon its bass line, there are thirty-two parts in the work, in ten groups of three: intellectual, emotional, and physical, as Schiff describes them; that is to say, a character piece, a technically virtuosic toccata, and a canon, which is always the last of the group of three. The first canon begins at the unison, and each subsequent canon is one interval wider, canon at the second, canon at the third, and so on. All the pieces are in the key of G, twenty-seven in the major, and three in the minor. The metre, however, is varied.

The first variation is the first of the virtuosic variations in each of the groupings of three, the other two being the reflective and canonic. To my ear the bass line of the aria is entirely apparent in this variation. There are some interesting presentations chosen by Bach, the bass of the first three bars of its second part is identical rhythmically to those of the first three in the first part; there is a wonderful cascade in bars 4 and 5 of the second part; and an elegant splendour of notes in the right hand of bars 9 and 10 that emulate the construction of the bass in the first part’s bars 9 through 12; brilliantly rising tension, driven by the bass line, in bars 13 and 14 of the second part; to conclude the variation in a quick falling in bar 15 to the concluding bar in contrary motion, as is the instance in the concluding bar of the first part. As to tempo, I find I prefer the quick.

Variation 2. This is the first of the reflective variations. It is remarkably satisfying in both sound and structure. It has three voices. Beyond the presence of the bass progression upon which the work is built, there are three other prominent characteristics. First, the presence of the opening bar’s rising 4th is increasingly prominent throughout, appearing most clearly again in bar 3, and in the second part of the variation, yet more frequently (bars 17, 24, 27, and 30). Second, there is a recurrent pattern throughout of four descending scalar notes, always on the second beat of the 2/4 metre. This is particularly enhanced in its effect when it becomes supported by a high rising bass in bars 9-11. Third, at bar 5 Bach introduces an undulation of three notes, always a half beat after the primary pulse of the bar. It always stays within the compass of a 3rd. It invariably and persistently occurs immediately before any of the four note scalar descents and travels amongst all the three voices. All three elements are combined in bars 30-31 before the final cadence in bar 32.

Variation 3. Canone all’Unisono. 12/8. Two elements of propulsion are immediately apparent. In the bass, bars 1-2, Bach writes even groups of three 8th notes, quickening in bar 3 to even groups of continuously flowing 16th notes to bar 16. In the soprano and alto voices, in the right hand, the canon’s subject begins with a dotted quarter note followed by a flow of six 16th notes, a structural interplay developed throughout, so that the longer notes in the right hand seemingly slow the flowing movement of the bass. All this is modified in the upper voices in the variation’s second half to an uninterrupted constancy of a combination of both note lengths. Further, the second part of the variation, bars 17-23, often invert this relationship and effect of note lengths, not from bar to bar, but cleverly, within the bar. In addition, Bach also inverts the canon in all the voices, the inversions increasingly deft in the second part of the piece. It is a consummately accomplished composition, and for the awareness of the listener, better discerned when heard than when reading words about. The impression on my ear also instills a resonance of how Bach chooses to apply similarities of patterns; in this variation its first bar brings to mind the first bar of the sinfonia of cantata 156, and even more gracefully, the entire largo of the harpsichord concerto BWV 1056, which derives from the sinfonia of the cantata.

All my publications are available on Amazon as well as at Apple, Kobo, Nook, and other international distributors.